NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—The key to the longest-range kill chains is to shorten the distance data has to travel by collating and processing it as close as possible to the place it is generated, a panel of industry experts and executives said at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference on Sept. 22.

Long-range kill chains entail platforms shooting without being able to physically see the target. That’s particularly difficult for an aerial target, that is typically more than 350 nautical miles away, hidden by the earth’s curvature, said Scott Jobe, a retired Air Force major general who is now a senior executive at Phantom Works, Boeing’s advanced research, development and prototyping division.

“We need to develop targets and then get that information back on a timescale that’s relevant,” Jobe said.

In such a scenario, sensors that might be hundreds or thousands of miles away or in space have to provide data to shooters, who will use it to track and fire on the target, explained Jobe, “That is not an easy task to undertake. Pick something on the other side of the planet, … track that target, maintain custody of that target, then fuse that data to include combat ID, and get that data to the shooter who’s going to engage.”

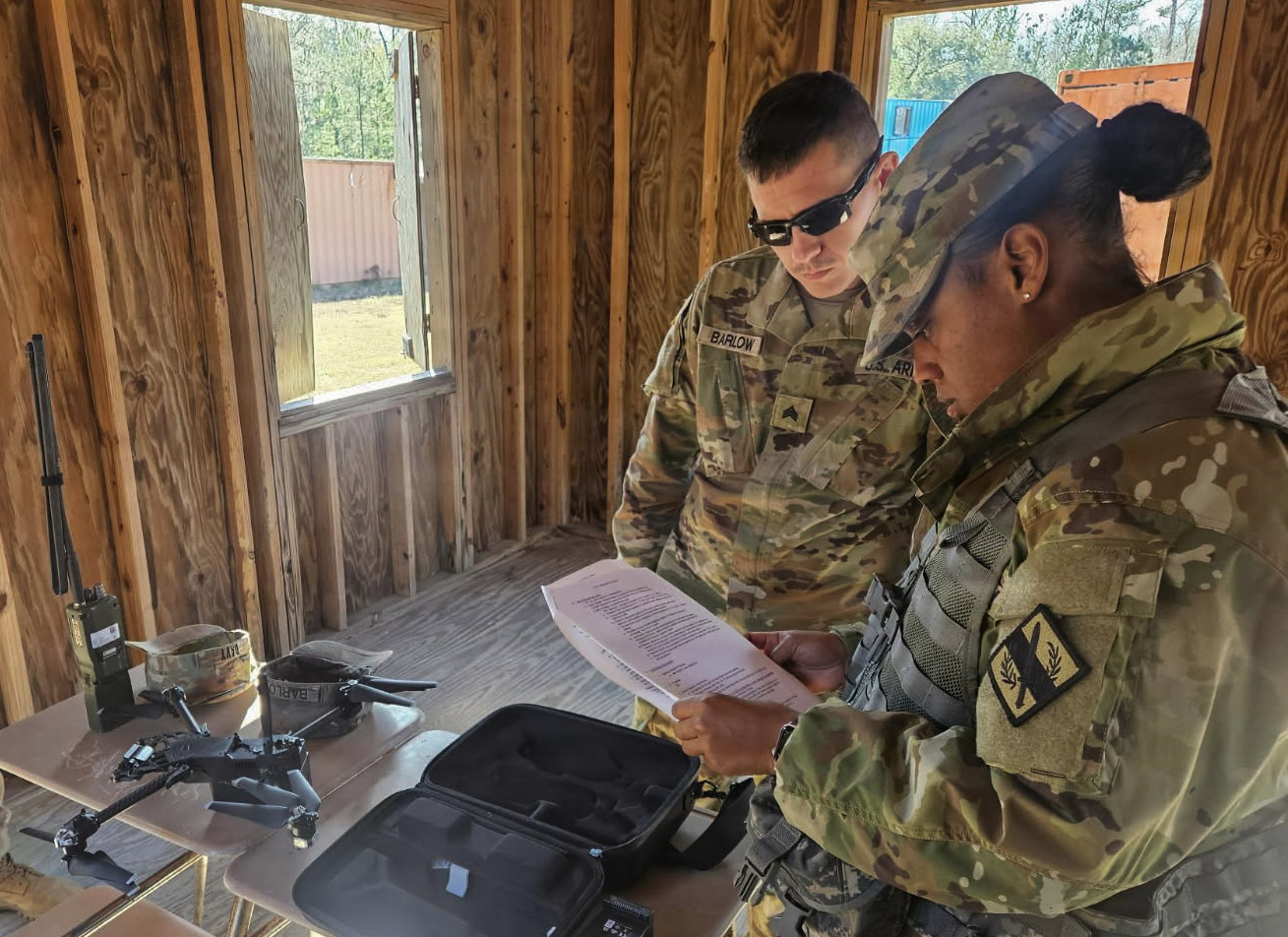

In some cases, the shooter might be on the ground, a tactical unit with disrupted connectivity or limited bandwidth, added Michael Geist, vice president for product management at SES Space and Defense, the Virginia-headquartered U.S. subsidiary of Luxembourg-based satellite operator SES.

If the unit requests information about a potential target nearby, “an Earth observation satellite can receive that tasking and can take those pictures, can transport those from orbit,” said Geist. But that’s where it gets complicated, because the raw images are much too large for the unit on the ground to receive them. A way-station is needed to “digitize that image, process it at the edge, in space, and redeliver that image in a fashion that makes sense for the limited capacity of, let’s say, a tactical UHF radio, to the user on the ground.”

That process could happen in “seconds to a minute,” Geist said.

The alternative would be to bring the data to earth for processing, and then get it to the shooter, probably by sending it back into space again. “What you want to avoid is having four or five or six hops and processing on the ground to make all that happen,” Geist said. He added that such a process typically creates latency of 10-20 minutes or more, creating the risk that the data is stale or outdated by the time it reaches the shooter.

Doing the processing at the edge creates “a massive increase in capability for the warfighter,” he concluded.

Processing at the edge also saves bandwidth, said Tyler Saltsman, cofounder and CEO of Edgerunner AI, an 18-month old startup developing on-device, localized, and offline generative AI for use by the military. He said Edgerunner is working with the Navy to develop an on-board AI tool that would ingest all the data available from the ship’s sensors and help Sailors make sense of it. “What we learned is they can generate over 150 terabytes a day of sensor data, but 90 percent of it is noise,” Saltsman said. Sending all that data back to a central collection point for processing would be an extremely inefficient use of limited bandwidth. “Bringing the AI to the data”, and doing the analysis on the ship obviates the need to send all that noise back to the rear, he said.

Ai at the edge could also be used to make data easier to query, Saltsman said. Edgerunner is working to make all that ship’s sensors’ data, once it had been filtered from the noise, queriable via natural language questions posed to a specialized generative AI chatbot.

“Rather than using tools that are just ingest machines which only give you insights, which is what we have today—and the problem with insights is you can interpret them many different ways—why not have AIs actually speak this language? Now we can translate between human language and machine sensor data language, and now I can really understand what I need to do,” he said.

Making data easier to handle and query is a key capability for long-range kills chains and multi-domain ISR, said Patrick M. “Mike” Shortsleeve, a former Air Force senior intelligence official and now vice president of strategy and business development for General Atomics.

“I had 28 years in the Air Force doing ISR. … I know that data just falls on the floor and doesn’t get looked at,” he said. “The issue is, there’s so much data out there,” he added, too much for any human to analyze.

“We can’t just rely on human brain power and fusion occurring between the ears like we have been,” he said.

Being able to make data “smarter,” or putting it “in more natural forms that we can work with—that’s going to accelerate the ability to do this.”

The post The Key to Long Range Kill Chains? Short Distances for Data, Officials Say appeared first on Air & Space Forces Magazine.

AFA National, Joint All-Domain Command and Control, Technology, edge computing, edge processing, Edgerunner AI, General Atomics, Long Range Kill chains, Maj. Gen. R. Scott Jobe, Michael Geist, Patrick Shortsleeve, SES Space and Defense, Tyler Saltsman

Air & Space Forces Magazine

[crypto-donation-box type=”tabular” show-coin=”all”]