Dirty hydraulic fluid and freezing weather led to the loss of an F-35 stealth fighter in Alaska this winter when its landing gear froze and convinced the aircraft’s computer that it was on the ground rather than in-flight.

The pilot lost control of the aircraft, ejected, and walked to an ambulance under his own power, but tail number 19-5535 was not so lucky, spinning wingtip over wingtip before crashing on the airfield in a fireball that was captured on video and posted to social media.

On Aug. 25, the Air Force released its investigation into the Jan. 28 crash, a total loss valued at $196.5 million, according to the report.

The temperature was about zero degrees Fahrenheit when the F-35 taxied out of its weather shelter for an air-to-air combat training sortie at about 10:42 a.m. local time. The pilot was an old hand with nearly 1,700 flight hours on the A-10 attack jet and 555 hours on the F-35. The first 40 minutes of this mission were spent on the ground waiting for the five other F-35s in the sortie to troubleshoot minor issues after engine start.

That 40 minutes gave the water-logged hydraulic fluid coursing through tail number 19-5535’s nose landing gear time to freeze, which was why things went awry shortly after takeoff at 11:22 p.m. The nose landing gear did not retract properly, and when the pilot tried extending the gear back out, the wheel itself was canted to the left, since the lack of full extension caused a misalignment that prevented the wheel from locking into place.

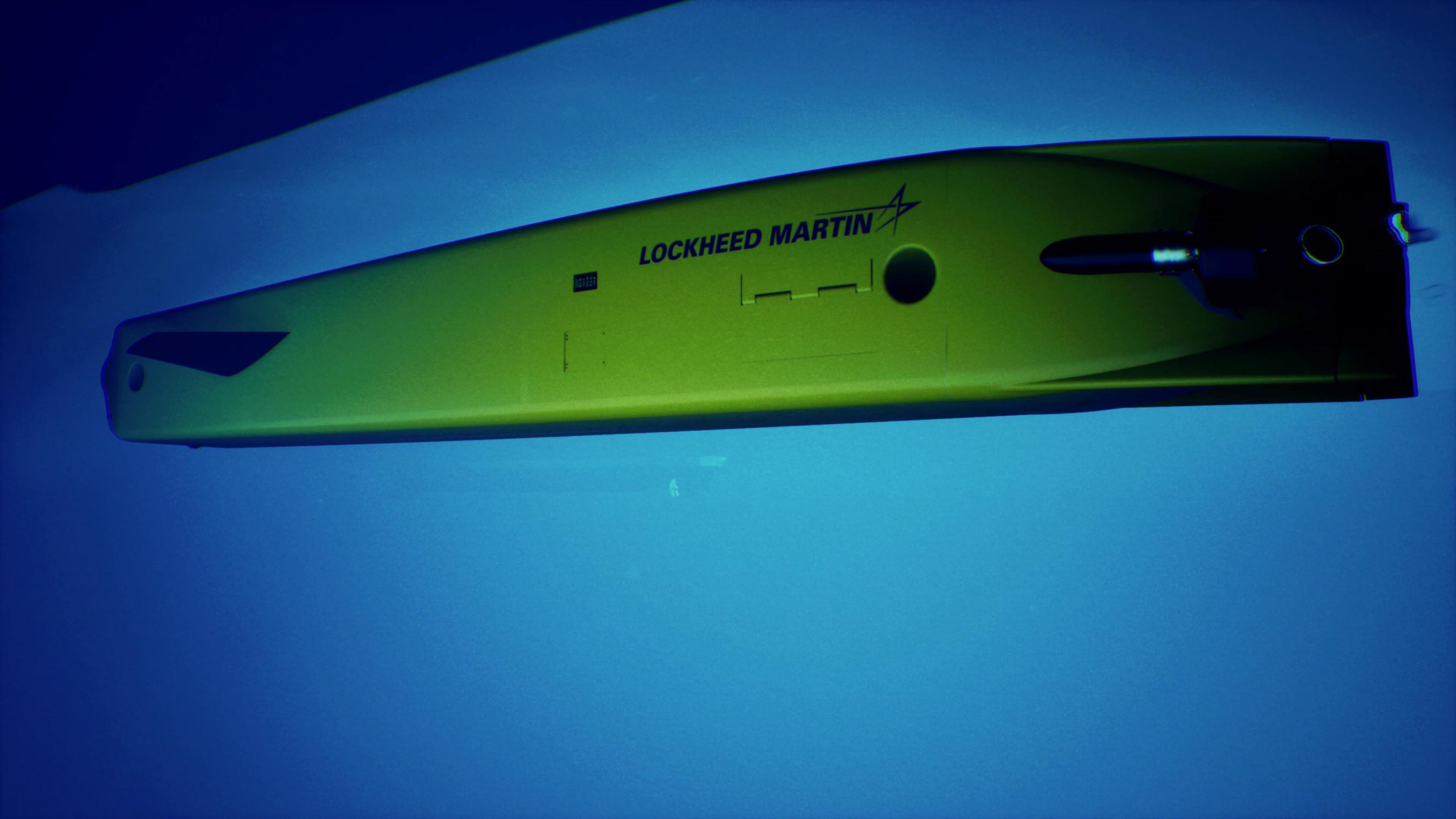

Not sure why his landing gear was faulty, the pilot and his wingman circled the airfield at 9,500 feet for about 50 minutes while the pilot called with flying supervisor in the air traffic control tower, who in turn set up a call with engineers from aircraft manufacturer Lockheed Martin.

The group decided to try a touch-and-go, where the aircraft touches down, then lifts off again without stopping. The hope was that the brief landing might straighten out the nose gear and reduce the risk of a rollover or runway departure when landing for real.

The pilot tried a touch-and-go at 12:18 p.m., but no luck. The conference call suggested a second, faster touch-and-go to see if it would center the nose wheel. But by now the ice buildup prevented both the nose and right main landing gear from fully extending or retracting. That confused the sensors which detect when the aircraft’s weight is on its wheels, making the computer start to think the F-35 was on the ground.

The F-35 touched down again at 12:48 p.m. Except now enough ice had formed on the left main landing gear that it could not fully extend, convincing the left gear sensor that it too was on the ground. With all gear sensors in agreement, the F-35 computer was convinced it was on the ground and shifted from in-flight control laws to on-ground control laws, despite flying at more than 250 miles per hour.

The pilot experienced “significant oscillations” and the aircraft did not obey the pilot’s control inputs, so he ejected just 372 feet above the runway. The jet continued climbing to 3,205 feet before stalling and crashing, passing the pilot drifting under parachute on the way down.

Enough of the landing gear survived that investigators found its hydraulic fluid was actually 30 percent water, which allowed it to freeze at a higher temperature.

Both the barrel the hydraulic fluid came from and the servicing cart used to put it in the aircraft tested at more than double the limit for particulates in hydraulic fluid. The 355th Fighter Generation Squadron was short-staffed, without a dedicated hazardous materials program manager, investigators found. The barrels were not locked, the servicing of the cart went unsupervised, and the pump atop the barrels had no thread sealer, which could allow water in. Records for tracking which equipment was used and when were patchy.

“These are significant lapses in following procedures that indicate an overall lack of discipline,” investigators noted.

Just nine days later, on Feb. 6, a second F-35 encountered the same problem when its landing gear could not fully retract or extend due to frozen, water-logged hydraulic fluid, but that aircraft spent less time outside in warmer temperatures and landed uneventfully. In fact, the pilot did not notice that the nose wheel was also canted to the left, showing that the Jan. 28 pilot could have landed safely rather than try two touch-and-gos.

Investigators credited the mishap pilot, wingman, engineers, flight supervisor, and senior operations group commander who helped them navigate an unforeseen maintenance problem. Still, they said conference call participants on the ground could have consulted an April 2024 notice from Lockheed Martin that landing gear weight sensors could lead to aircraft control issues, particularly in extreme cold weather. With that knowledge they could have advised a full-stop landing or a controlled ejection rather than a second touch-and-go.

The post Contaminated Hydraulic Fluid, Ice Led to Fiery F-35 Crash in Alaska appeared first on Air & Space Forces Magazine.

Air, 354th Fighter Wing, accident investigation board, aircraft maintenance, aviation mishap, Eielson Air Force Base, safety

Air & Space Forces Magazine

[crypto-donation-box type=”tabular” show-coin=”all”]