Flying a stealth bomber loaded with bunker-busting ordnance around the world and back in 37 hours might sound like science fiction. But in reality, executing such a mission in the B-2 Spirit depends on mundane details: topping off the gas tank, staying hydrated, avoiding thunderstorms, and being careful not to overload a small toilet in the 25-square-foot crew compartment.

At least, that was retired Air Force Col. Mel Deaile’s experience when he and his co-pilot, Brian Neal, flew a record-setting 44.3-hour B-2 sortie to strike targets in Afghanistan on Oct. 7, 2001.

“Instead of looking long-range, ‘Hey, we’re going to Afghanistan,’ it’s more about making sure we get to the next air refueling on time,” Deaile told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “We can’t miss this air refueling, otherwise this mission will be short-lived.”

On June 22, 14 Airmen aboard seven B-2s joined Deaile and Neal atop the list of aviators with the longest nonstop stealth bomber sorties when they struck Iranian nuclear sites in a bid to delay Tehran’s ability to build a nuclear weapon.

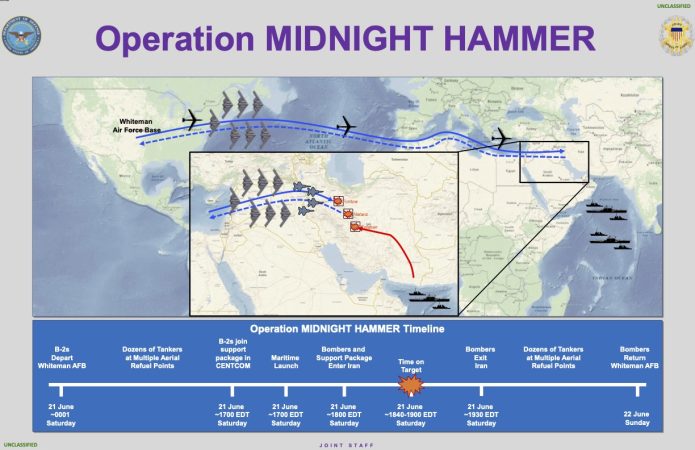

Dubbed Operation Midnight Hammer, the mission marked the second-longest B-2 flight in the plane’s history, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine said. About 125 U.S. planes, including the B-2s and fourth- and fifth-generation fighters, participated in the mission that dropped 75 precision-guided munitions on three sites across Iran. U.S. submarines launched Tomahawk cruise missiles in coordination with the air assault.

The B-2s dropped 14 Massive Ordnance Penetrators on the sites at Fordow and Natanz in the first operational use of the 30,000-pound weapons. Taking off from their home at Whiteman Air Force Base, Mo., on June 21, the crews flew east over the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, struck their targets in Iran, then turned around and flew back to Missouri, filling up at dozens of tankers along the way.

The operation was “planned and executed across multiple domains and theaters with coordination that reflects our ability to project power globally, with speed and precision, at the time and place of our nation’s choosing,” Caine said at a press conference following the attack.

The circumstances were similar 24 years ago, when Deaile and Neal climbed into a B-2 nicknamed the “Spirit of America” and took off into the night toward southwest Asia. Prior to that, Deaile had flown a 25-hour sortie in a B-52 and a sat in a simulator for about 20 hours nonstop, but none of his previous cockpit time rivaled the task ahead.

“There is no preparation, no simulator requirement for a 44-hour mission,” he said.

The aircraft was loaded with 16 Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAMs) to destroy air defenses, but 70 percent of the targets changed mid-flight, he said. The switch forced the pilots to reprogram the JDAMs and redo other calculations to ensure mission success.

“You’re reviewing target folders, reviewing timing, checking our fuel consumption so that we’re not going to run out of gas over the Pacific,” he said.

That may have occurred during the Iran mission, too. Another former B-2 pilot told Air & Space Forces Magazine that, once over the target area, B-2 pilots can use the bomber’s radar to create target coordinates that are “usually even more precise than intel has provided.”

Flying high for that long can also leave people parched. Deaile and Neal drained multiple water bottles throughout the flight—but the aircraft’s chemical toilet was too small to hold 44 hours’ worth of output. Instead, the Airmen used “piddle packs,” plastic bags filled with a kitty litter-like substance that turns urine into a gel.

“We’re filling up two piddle packs per hour, and piddle packs weigh so many pounds, so we were trying to figure out how many pounds of solidified pee we were going to have to offload from this aircraft when we finally landed,” Deaile said.

The answer? About 100 pounds.

“Those are things that you do to pass the time,” he said.

Rest is another issue. While many civilian airliners and some military aircraft bring multiple crews for long-haul flights, the B-2 has just two pilots for the entire mission. Deaile recalled one person was often unconscious in a sleeping bag atop a modified Army cot behind the ejection seats.

It wasn’t high-quality sleep, he said, “but at that point, any sleep is good sleep.”

Both pilots had to be in their seats during critical phases of flight, such as air refueling, so the two switched places after meeting a tanker every four or five hours. To keep themselves going, the crew brought coffee, water, sandwiches, pretzels, and pre-packaged meals designed specifically for in-flight consumption. But sitting in a cramped cockpit for prolonged periods doesn’t tend to work up an appetite, Deaile recalled.

“You’re not really burning calories,” he said.

His crew had the advantage of flying in daylight across the Pacific, so the sun didn’t set until they approached Pakistan. That meant their bodies didn’t start releasing melatonin, a hormone which helps the brain prepare for rest, until late in the flight.

The crews on this month’s Iran strike may have had a more difficult time, since they flew east into the darkness, Deaile said. The Airmen could have taken amphetamines called “go” pills that are commonly used by troops to stay alert on long flights.

“It definitely accelerates the heart rate,” Deaile said. “It is not a fun feeling.”

Last weekend’s B-2 mission and those flown in the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks share another key feature: Their crews were charged with the responsibility of completing a high-profile mission ordered by the president of the United States.

“We practiced crew procedures, the timing and coordination, because you want to eliminate the possibility of things not going to plan as much as you can,” Deaile said.

His mission stretched about two hours longer than expected after local air operations coordinators asked them to fly back over Afghanistan to use their last four JDAMs on a few remaining targets. Then it continued another 15 minutes when the B-52 landing ahead of them at Diego Garcia, a small island in the Indian Ocean, suffered an emergency. Around the airfield the B-2 went.

“We looked at each other like, ‘Can we not get this thing on the ground?’” Deaile recalled. When they finally touched down, he said, “we were just glad to be back on terra firma.”

The crews who flew the Iran mission no doubt felt the same relief—and they’re unlikely to be the last. Air Force officials expect to see similarly long flights as the service prepares for a potential conflict with China in the vast Pacific.

Those long-haul sorties would disproportionately affect the tanker and transport crews tasked with ferrying gas, equipment, and troops around the region each day.

To practice, a C-130 transport last year flew 26 hours from Texas to Guam, while a KC-46 tanker flew a nonstop 45-hour lap around the world from Kansas a few months later. Air Mobility Command aims to help crews maximize their performance over long sorties with sleep pods, wearable health monitors, and reflex tests. At the 2023 iteration of Mobility Guardian, the Air Force’s major biennial mobility exercise, the command relaxed its rules barring “go” pills so Airmen could get the jolt they needed to rush equipment to the Pacific.

“In an era of great power competition, crews need the ability to operate longer than they have in the past,” one of the KC-46 pilots said last year.

That task will likely grow more difficult as aircraft like the B-2 age. The Spirit of America was just 8 years old when Deaile flew to Afghanistan, he said. Now that the aircraft are 24 years older, deploying one-third of the B-2 fleet across the world and back on the same night—plus sending out a few more over the Pacific as a decoy—is itself an accomplishment.

“That’s a monumental task. A huge hats-off to the maintainers and logisticians who got those jets ready,” Deaile said. “The maintenance need is not going down as they get older.”

The post 15 Tons of Bombs and 1 Tiny Toilet: Around the World on the B-2 Spirit appeared first on Air & Space Forces Magazine.

Air, B-2, Iran, Massive Ordnance Penetrator, maximum endurance operations

Air & Space Forces Magazine

[crypto-donation-box type=”tabular” show-coin=”all”]