To deploy during wartime, the U.S. military will rely on civilian infrastructure that’s vulnerable to cyberattack by America’s adversaries, current and former Air Force officials and other speakers told an airport cybersecurity conference last week.

Dozens of airports host both civilian and military flights, and that mingling of facilities can create technical vulnerabilities and policy gaps enemy hackers could exploit, speakers told the “Defend the Airport” event on June 18.

Just a few days later, that threat was underscored when the Department of Homeland Security issued a National Terrorism Advisory System alert, warning of possible Iranian cyberattacks in retaliation for U.S. bombing raids on Iran’s nuclear program.

Iran isn’t the only concern. U.S. intelligence agencies have publicly accused the Chinese military of hacking into the IT systems of American power companies and other critical utilities providers. Their aim is “pre-positioning”—lurking undetected in the quiet corners of a computer network, so they can interrupt electricity, water, and other vital supplies in the event of a war.

“The adversary doesn’t care if it’s the federal government. It doesn’t care if it’s a commercial property. It doesn’t care,” Department of the Air Force Principal Cyber Advisor Wanda Jones-Heath said.

Yet those trying to defend aviation infrastructure against foreign hackers have to care who owns it, and the issue highlights a policy challenge. Private or civil-owned and -operated domestic infrastructure, like airports, will be key to how the military deploys and operates in a future war—so how should the U.S. protect it from enemy cyberattacks during peacetime?

Dual-Use Infrastructure

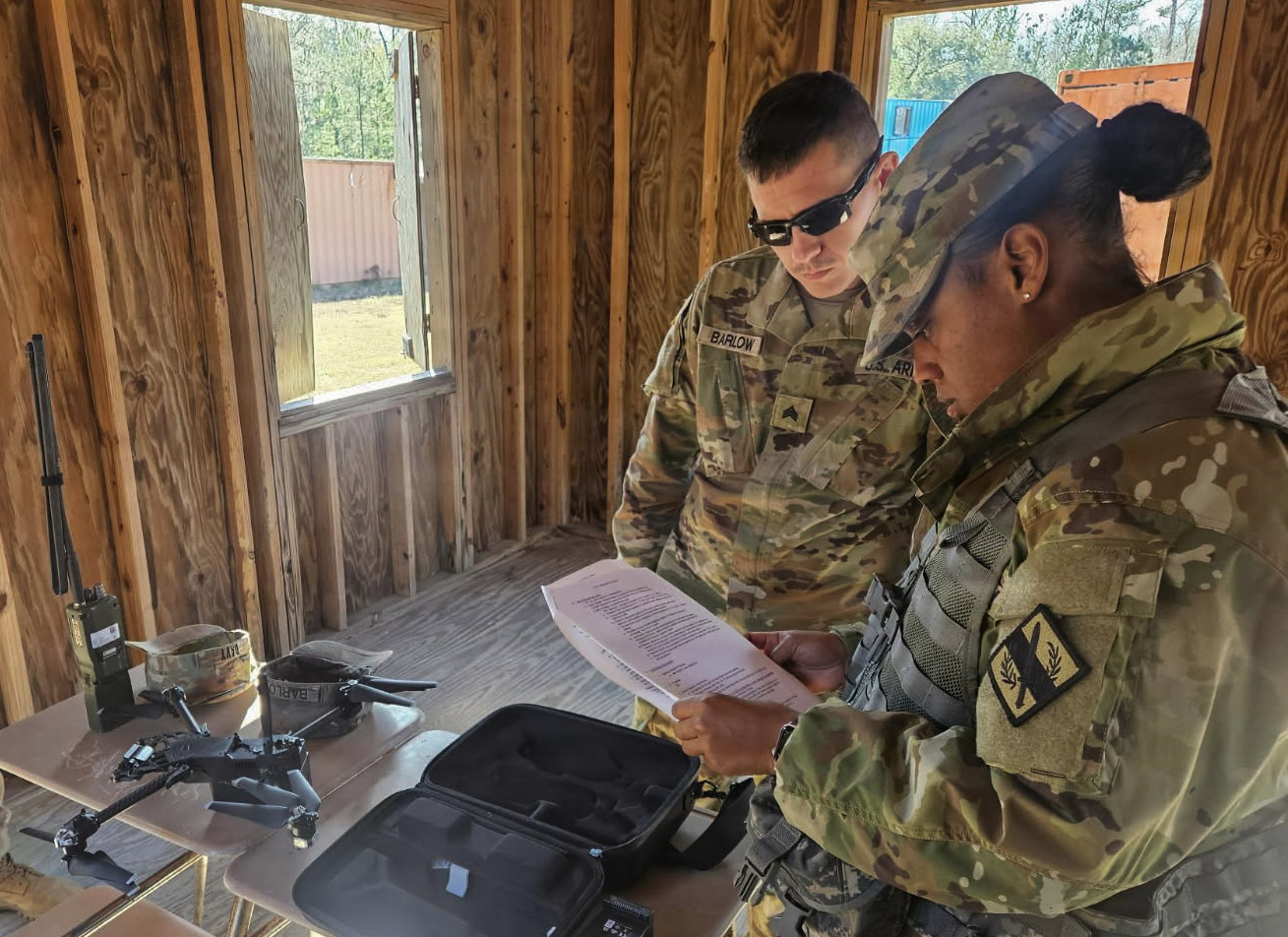

In a major conflict with China, the U.S. would have to move tens of thousands of troops—not to mention vehicles and aircraft—quickly to ports and airports for deployment to the Pacific. The sheer scale would require the military to rely on civilian aviation, explained retired Rear Adm. Mark Montgomery, the director of CSC 2.0, a nonprofit that continues the work of the congressionally chartered Cyberspace Solarium Commission.

“For moving the numbers [of troops] that we’ll need to fight a major war, we’re going to use our commercial rail, port, and aviation systems for 90-plus percent,” said Montgomery, a former staffer for Sen. John McCain and executive director of the original CSC.

This reliance makes the civil aviation system a potential target for an enemy sneak attack. “U.S. adversaries know that compromising this critical infrastructure through cyber and physical attacks would impede America’s ability to deploy, supply, and sustain large forces,” a recent report from CSC 2.0 warns.

A ransomware infection at Seattle-Tacoma Airport last year showed the level of disruption possible from a single, partially successful cyberattack. On Aug. 24, “unauthorized activity” was detected in the IT network of the Port of Seattle, the municipal agency which runs the airport, according to congressional testimony from Lance Lyttle, the airport’d aviation managing director.

The hackers’ malware, and “responsive actions” from the network’s security team, impacted services like baggage label printing and reading, shared check-in and ticketing, public WiFi, airport information display boards, and the airport website. The Transportation Security Administration’s separate network, and those of major airlines with their own IT infrastructure, were unaffected.

Nonetheless, operations at the airport did not return completely to normal for three weeks, according to the Seattle Times, and thousands of passengers were separated from their luggage, which had to be labeled and sorted by hand. More than 170 flights were delayed following the incident, local TV station FOX 13 reported.

IT vs. Operational Tech

There’s another target beyond the IT and computer networks at airports, said Eric Bowerman, assistant vice president for cybersecurity at Dallas Fort Worth International Airport. Increasingly, airport managers are worried about hackers targeting operational technology—think baggage conveyor belts, building access control systems, and lighting systems for the terminal and the runways.

Part of the issue, Bowerman said, is that the IT department often has little visibility into OT deployments. He joked that he sometimes only discovered new OT systems by noticing that they had been installed. “Whenever I walk through the terminals, there’s always a new blinking light somewhere that I have to worry about securing,” he said.

As well as being managed separately from IT, OT systems have to be 100 percent reliable and often employ technology that is years or even decades old and can’t always be protected by conventional cybersecurity tools.

Both IT and OT systems can be critical to flight operations and have to be protected from hackers, said Anthony DiPietro, the technical director for defense critical infrastructure in the NSA’s Cybersecurity Division. NSA, in addition to its signals intelligence role, has a second mission—defending national security-critical systems from foreign cyber warriors and online spies. That includes military airfields, DiPietro explained.

“If the Air Force or the Navy has an airfield, those systems that are necessary to conduct flight operations on that field would be candidates for concern by our teams,” he said, because without them, “that unit could not effectively execute the tasks that it has been ordered to do.”

Not all mission critical systems are obvious, DiPietro pointed out. For example, a hack on the weather reporting and forecasting data system “could … impede flight operations,” he suggested. “So all of those systems are candidates” for NSA protection.

Outside the Fence Line

The NSA’s operational cybersecurity role is limited to military bases, “inside the fence line,” as DiPietro said, but there are critical systems outside too.

Local power companies BGE and Exelon “supply power to numerous [military] bases around the area,” he pointed out. ”If they go away, what does that mean for those bases?” he asked. The NSA is seeking partnerships with vital service providers to address those “outside the fence line” issues, he said.

“You have to take state, local, and tribal governments in play too, because the entities that control the local utility providers, you have to work with them to then protect their systems so that the resiliency of the ‘inside the fence line’ unit is maintained,” he added.

One attendee at the conference, a retired Air Force C-5 pilot who is now a visiting professor at the National Defense University’s College of Information and Cyberspace, pushed back against the idea that a cyberattack could easily stop military flight operations at any airport.

“If I’m at war with China,” retired Col. Robert Richardson told the conference, “you’d be surprised how little I need” to safely land a massive C-5 cargo plane. “I need a clear runway, and someone on the ground to tell me where to park and take care of my cargo. That’s it.”

“This is a real issue and it’s important,” he told Air & Space Forces Magazine on the sidelines, “but it’s important not to get it overblown.”

The major hubs used by military flights, like DFW, are large enterprises that take cybersecurity seriously, he said. “These aren’t mom-and-pop operations. If something needs fixing, it gets fixed.”

Moreover, aviation enjoys the advantage of a technological culture that prioritizes safety, valued redundancy, and rigorous rule-following in critical functions, Richardson said: “The cyber guys would drool to have the kind of culture [in IT] that we have in aviation,” he said.

Shared Responsibility

The job of protecting vital civilian infrastructure so that it is available for military use in wartime is a shared responsibility between the private sector and federal, state, and local governments, especially when it comes to cybersecurity, explained Brian Scott, deputy assistant national cyber director for cyber policy and programs at the White House Office of the National Cyber Director.

“There is a wide range of folks that have responsibilities” for cybersecurity, he said, adding the owners and operators of critical infrastructure have the “primary responsibility for self-defense” day to day, and doing what he called “due diligence” on their IT infrastructure.

“However, we don’t expect, and we can’t expect, every critical structure owner/operator to defend itself against nation state actors,” he added. “The federal government has responsibilities for defending the nation, obviously. So we have core responsibilities relative to that, but a lot of these things need to be done in a collaborative way with shared responsibilities.”

The military had done well inside the fence line, Montgomery said. He joked that critical infrastructure on military bases “is like Noah’s Ark—there’s two of everything.” By contrast, he believes the Pentagon’s efforts to secure dual-use civilian infrastructure are inadequate and siloed off from the broader efforts of the federal government to protect the nation from cyberattack.

The problem is especially critical because the U.S. civil and military air transportation systems are closely intertwined, even in peacetime, and would only be woven more closely together in a war.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration, the U.S. has 21 joint-use airports—military airfields also used with permission by commercial flights, and housing passenger terminals and other civilian infrastructure. The Air Force has 10 of these, including mid-sized regional airports like Charleston, the busiest airport in South Carolina. There are also 65 shared-use airports—owned by the federal government, usually DOD, but with a civilian airport also on site and sharing use of the runways and other facilities. Shared-use facilities include international terminals like Bangor, Maine, and Burlington, Vt. Finally, the Air National Guard has agreements in place to use a dozen more civilian airports including large regional centers like Jacksonville, Fla.; Pittsburgh; and Minneapolis.

Strategic Small Airports

All of these dual-use facilities are among the 520 U.S. airports certified by the FAA to service scheduled flights by commercial passenger aircraft carrying more than nine people. But there are more than 5,000 public airfields with paved runways across the U.S., noted retired Lt. Gen. Mary O‘Brien, a former deputy chief of staff for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance operations and cyber effects.

Many of these small non-certified airports are a lifeline for their local community, explained O’Brien, providing a landing strip for emergency medical services like organ transplant transportation, crop dusters, flight schools, and hobbyists.

Yet they also could be valuable for DOD. Many are converted military landing strips with runways as long as 10,000-15,000 feet—long enough to land the largest military and civilian aircraft. “Small does not equal the size of the runway,” she said. “They can become very strategic if we need them.”

The post Dual-Use Military and Civil Airports Face Cyber Threats—and Policy Challenges appeared first on Air & Space Forces Magazine.

IT Modernization, Operational Imperative 5: Resilient Basing, Operational Imperative 7: Readiness to Deploy And Fight, civil aviation, critical infrastructure, CSC, cybersecurity, infrastructure

Air & Space Forces Magazine

[crypto-donation-box type=”tabular” show-coin=”all”]