Data Centers Are A Repeat Of History In PA’s Coal Region

Authored by Jake Wynn via RealClearPennsylvania,

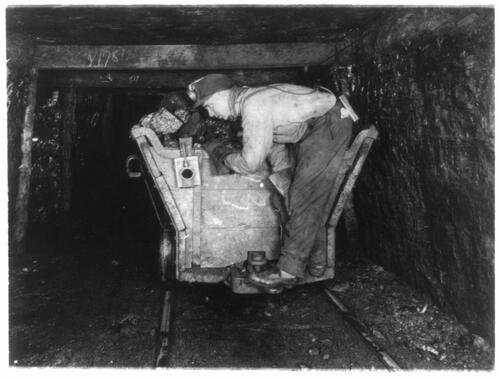

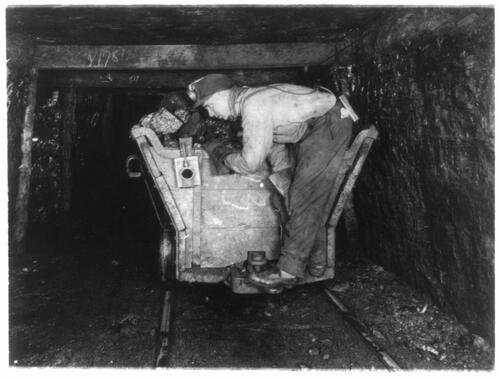

By the 1920s, Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal region was already living with the consequences of decisions made far from its towns and patch villages. The industry that had built the coal towns and cities of eastern Pennsylvania was no longer organized around mineworkers or the communities they lived in, but around efficiency, scale, and centralized control. Mechanization, electrification, and consolidation were already reshaping daily life above and below ground.

Coal companies framed these changes as modern necessities. In 1929, the president of the Philadelphia & Reading Coal & Iron Company (P&RC&I) explained declining production not as a crisis of employment, but as a problem of outdated infrastructure. The solution, Andrew J. Maloney argued, lay in “more flexibility in our producing units,” achieved through “the construction of two modern centralized breakers to electrify the mines tributary thereto.”

The new Locust Summit and St. Nicholas district breakers, authorized just before the stock market crash of 1929, embodied that logic. Electricity would streamline production, while centralization would reduce costs. Smaller collieries – especially those farther from rail lines or markets – would simply disappear under this scheme.

They did. As mammoth central breakers came online, operations of the P&RC&I in places like Tower City, at the western edge of Schuylkill County, and other outlying communities were shuttered. Instead of work migrating slowly and evenly toward the centralized facilities, jobs vanished completely in many communities.

According to historians Thomas L. Dublin and Walter Licht in their 2005 book, Face of Decline, about this topic, Mahanoy City saw six of seven collieries closed. In Shamokin, four of five mines stood idle.

They also noted that in Lykens, the town’s lone mine, the Short Mountain Colliery, was shut down entirely. The promise of “efficiency” translated into widespread unemployment across the anthracite coal counties. The coming of the Great Depression worsened the matter, as companies like the P&RC&I had overleveraged themselves constructing the massive centralized breakers, forcing more closures to cut costs to meet payments on their debt.

Strip mining deepened the rupture. It required fewer workers and moved relentlessly across landscapes that had once supported deep mines and densely packed communities. Combined with centralization, it ensured that even when coal was extracted, it no longer sustained local labor at the scale needed for deep mining operations. By the early years of the Great Depression, the anthracite economy had collapsed into something unrecognizable just a decade earlier.

This situation started a pattern that saw the sudden collapse of the economy in communities all over the coal region. In the decades that followed, attempts at revitalization and to find new investment largely failed to replace what coal had done to build these communities. People began to leave the region. Some found new purpose: Mauch Chunk for example re-invented itself as Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania in the 1950s and leaned into tourism to replace the industries that once built the town.

But for most communities, that struggle for purpose and a stable economy went on into the late 20th and early 21st centuries. New investment did come from companies and corporations seeking cheap land and ready access to interstate highway corridors with easy access to metropolitan areas like Philadelphia and New York. Since the early 2000s, warehouses and fulfillment centers have become essential to the coal region’s economy.

Yet now, a century after the beginning of the end of the namesake industry in the coal region, there are some unsettling parallels to the past.

The warehouses and fulfillment centers sitting on reclaimed mine land are often the largest employers in many coal region communities. Once again, outside capital has arrived with promises of stability and modernity. As happened 100 years ago, efficiency is the guiding principle. Automation and artificial intelligence already threaten to reduce these jobs, just as electrified mines, strip mining, and centralized breakers once did. Proposed data centers – vast, energy-intensive, and labor-light – signal another shift toward consolidation without community security.

History offers no easy answers nor perfect comparison, but it can offer some past examples in strange new times.

When jobs disappear suddenly and at scale, the consequences echo for generations. The collapse of large-scale mining in the 1920s and 1930s reshaped the coal region for the next hundred years. The choices made today – about automation, land use, and whose interests are prioritized – will shape the next century just as profoundly.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 02/11/2026 – 12:05

ZeroHedge News

[crypto-donation-box type=”tabular” show-coin=”all”]