Why Parents Are Suing Snapchat Over Fentanyl Deaths

Authored by Janice Hisle via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

WASHINGTON—Over and over, Amy Neville forces herself to tell people what happened to her 14-year-old son.

“I relive it. … I’m out there sharing the hardest thing that’s ever happened in my life,” she said. “It’s worth it, because I know we’re saving lives.”

Neville, 52, wiped away tears as she spoke those words during an interview with The Epoch Times on June 23. That day marked five years since her son, Alexander Neville, unknowingly ingested fentanyl and died—a tragedy that could easily befall any family, she said.

Through the nonprofit Alexander Neville Foundation, the grieving mother shares her personal pain with other parents. By her estimation, Amy Neville has given a couple hundred presentations in person and online; about 300,000 people have heard her warnings about the dangers that lurk on social media, leading to deaths such as Alex’s.

Neville also serves as the lead plaintiff in a groundbreaking court case that could affect the way Big Tech operates in the United States.

She believes that changes are needed to prevent many deaths among young people who, like Alex, flock to Snapchat and other online platforms.

Neville and her husband are among 63 fentanyl victims’ families suing Snapchat. They allege that the platform is a defective product and a public nuisance and that it should be held responsible for fentanyl overdose deaths, poisonings, and injuries.

Snap Inc., parent company of Snapchat, “vehemently denies” the allegations, a judge noted.

In the suit, the Social Media Victims Law Center represents dozens of families whose children “died of fentanyl poisoning from contaminated drugs purchased on Snapchat,” Matthew Bergman, the Seattle-based center’s founding attorney, told The Epoch Times.

Snap did not respond to a request for comment.

Life Changed ‘Like a Light Switch’

Five years ago, the Nevilles were living in Aliso Viejo, California, a tree-lined suburb of Irvine that ranks among the state’s safest communities.

Neville was running her own yoga studio; her husband, Aaron, was working as a website developer. They were both in their 40s, parenting their daughter Eden—a “brainiac” who loved school—and their son Alex, a “super smart” boy who hated homework but loved history, skateboarding, and gaming, according to Neville.

They were an “ordinary” middle-class family, she said.

The mother of two said she remembered thinking that the biggest threat to her asthmatic son was probably the COVID-19 respiratory virus that was then spreading.

But that was life during the period Neville calls “the Before”—the era before the day that changed everything instantly, “like a light switch” being flipped, she said.

On the morning of June 23, 2020, Neville went to awaken Alex for a dentist appointment. Her knock on his bedroom door yielded no response.

So she entered the room. She confronted a horrifying sight: Her son, reclining in his favorite red beanbag chair—seemingly asleep, except his skin had turned cyanotic blue.

Clearly, he was dead. But as a mother, Neville could not let go of hope. Maybe her firstborn could be revived, she thought.

Neville blocked Eden, then 12, from seeing her older brother in that condition. Then she called for her husband, who performed CPR while she spoke to a 911 operator via cellphone.

When medics arrived, they took over CPR, strapped Alex to a gurney, and took him to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

The Nevilles were gobsmacked. But a clue soon surfaced.

“There’s a pill left behind in the room,” an investigator told Neville. She had not noticed it.

The unidentified pill was turned over to the federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

“That’s when we learned about the fentanyl,” she said. “The pill tested positive for fentanyl.”

About Fentanyl—and Snapchat

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that can be prescribed for managing severe pain or for anesthesia. But it can also be risky because it is far more powerful than morphine, is highly addictive, can interfere with breathing, and can cause confusion, nausea, and drowsiness. Abusers may be drawn to it because it can create a sense of euphoria.

While doctors can currently continue prescribing fentanyl, a Schedule II Controlled Substance, under tight controls, Congress recently passed a bill that permanently classified “fentanyl-related substances” as Schedule I drugs with “no currently accepted medical value.” Offenses involving those substances carry strong criminal, civil, and administrative penalties.

After President Donald Trump signed the bill on July 16, the Halt All Lethal Trafficking of Fentanyl Act became law.

Because fentanyl is cheap to produce, illicit drug dealers add it to other substances. They also substitute fentanyl for buyers’ requested drugs, despite how deadly it can be.

Even a pencil-tip-sized amount can prove fatal, as emphasized in the national “One Pill Can Kill” public awareness campaign. The DEA launched that program four years ago to combat dramatic increases in deaths related to counterfeit prescription painkillers; agents have been seizing millions of these fake pills each year. So far, that number exceeds 45.7 million, according to the agency’s website.

Fentanyl has been blamed for more deaths among teens and young adults than “COVID, car accidents, or even suicide,” according to the Snapchat lawsuit that Bergman filed along with C.A. Goldberg, a law firm in the New York City borough of Brooklyn that focuses on cases against tech companies.

The Neville suit argues that Snap contributed to an “epidemic” of fentanyl deaths.

“Social media platforms and Snapchat in particular … allow drug dealers to ply their deadly trade at scale with relative anonymity, with relative legal immunity,” Bergman said.

He said stemming the fentanyl crisis at the national level requires not only cutting off the drug pipeline from foreign countries, but also “holding social media companies accountable, because they’re the primary vehicle” for the distribution of fentanyl-contaminated pills.

In 2023, more than 107,000 Americans died from drug overdoses, according to data from the DEA. Nearly 70 percent of those deaths were attributed to opioids such as fentanyl.

Fentanyl deaths of children aged 18 and younger surged more than 30-fold between 2013 and 2021, according to data published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2023.

More than 100 million Americans use Snapchat, including more than 20 million teenagers, Snap co-founder and CEO Evan Spiegel told Congress in 2024.

Looking Back

Alex’s death “blindsided us,” Neville said, even though his tragic end, in hindsight, fit with a revelation the teen had made on Father’s Day, two days before he died.

Neville said she remembers her son confessing during a kitchen-table discussion: “I have got to tell you guys something. I wanted to experiment with Oxy. I got it from a dealer on Snapchat. It has a hold on me, and I don’t know why.”

Alex was referring to OxyContin—an addictive opioid. He admitted to using the street version of that drug on-and-off for a little more than a week.

Right away, Alex’s parents thanked him for disclosing his problem. They contacted a treatment center where they intended to enroll him.

The next day, Neville took her son to get a haircut.

It would be his last.

Neville remembers admonishing her son that day.

“Please don’t take any pills tonight,” she said.

He promised that he would not.

By the next morning, he was dead—after apparently taking what he thought was OxyContin.

Neville said that back then, it never occurred to her that the pills could be laced with—or replaced with—a deadly drug.

“We didn’t know about fentanyl,” she said. “Nobody was talking about it at the time, and no one was talking about the depth of social media harms.”

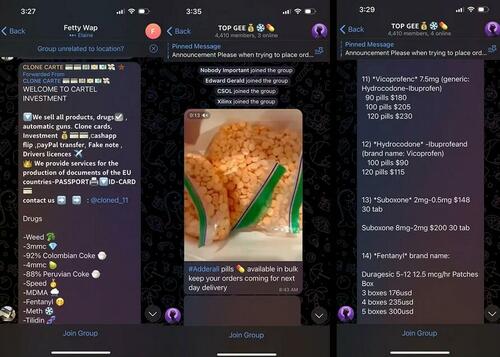

Neville had “spot-checked” her son’s social media accounts for any hint of sexual predators or bullies. But she was unaware of the emojis that teens and drug dealers use to trade coded messages about drugs.

Now Neville includes that information in her messages to parents as she traverses the nation.

Snapchat Features Debated

On Snapchat, users exchange “Snaps”—texts, videos, and photos—that can vanish after a specified time.

That disappearing-message feature is intended to maintain privacy and allow people to “express whatever’s on [their] mind at the time—without automatically keeping a permanent record of everything [they have] ever said,” Snapchat’s website states.

That is a big reason Snapchat appeals to users, according to the company. That feature also distinguishes Snapchat from other platforms. Snapchat’s logo—a stylized ghost—represents the ephemeral nature of its messaging system.

This disappearing act allows drug dealers and other predators to evade law enforcement—while widely promoting illicit drugs, critics say.

“It’s like you put your drug ad up on a billboard at Times Square … but the evidence disappears,” Bergman said.

The company’s website reads, “We work with law enforcement and governmental agencies to promote safety on our platform.”

The company also advises users that “some information may be retrieved by law enforcement through proper legal process.”

Snapchat has other features that are cause for concern, critics say.

Bergman alleged that Snapchat routinely connects “predatory drug dealers with vulnerable teenagers who are not seeking to purchase drugs.”

In its court filing, the company countered that it works hard to detect and intercept drug traffickers and responds rapidly to reported illegal activity.

In 2024, the company changed its Snap Map feature to improve safety. Now users’ locations are hidden by default—and parents can “see which friends their teen shares their location with,” the company stated.

Another point of contention is the allegedly addictive nature of social media platforms.

Some of the most brilliant U.S. minds formulate computer algorithms that analyze users’ actions and reactions. Then the system “feeds” people more content of the type that is likely to keep them mesmerized. The platforms also set up features designed to prolong usage. The longer a user stays on a platform, the more money-making advertising he or she is likely to see—boosting the company’s profits.

Snapchat, for example, rewards users with “Streaks,” scores based on repeat usage.

When parents take away teens’ phones, some have admitted to “literally crying on the floor … because their ‘Streaks’ will be interrupted,” Bergman said.

Read the rest here…

Tyler Durden

Sat, 08/02/2025 – 14:00

ZeroHedge News

[crypto-donation-box type=”tabular” show-coin=”all”]